“Women in the communities are active participants in building disaster preparedness”

The importance of women's leadership in disaster preparedness in the Philippines.

Lea says the lack of gender equality in decision-making has made it harder for women to be heard in disaster planning and in all aspects of Philippine society.

“Government agencies are usually led by men,” Lea says. “It makes the work challenging for women because there are a lot of barriers that prevent us from taking a lead role.”

Lea conducts evidence-based research which helps communities map their capacities and how different grassroots networks work together to reduce disaster risk. She says that women’s inputs in disaster planning are essential.

“Women in the communities are active participants in building disaster preparedness. We need to reach out to them and support them.”

“Women deserve opportunities because they have a lot to contribute,” Lea says. “They can help improve the way we do humanitarian, development work and disaster preparedness.”

Beyond the work mapping community organizations, Lea also looks at how vulnerable groups access services in disasters and identifies where there are gaps. The research gives data points to discussions that had previously been overlooked.

“Less than 1% of the population that experience disasters have access to a mental health support system,” she says. “It makes it challenging for people who endure the disasters not to have something or someone to support them.”

To address this, the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative is conducting a research on the MHPSS (Mental Health and Psychosocial Support) providers in the Philippines to understand the types of services they provide, identify the institutions they coordinate with and the support they need to better serve people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Not only is Lea’s research highlighting areas where greater coordination is needed but it is also challenging conventional narratives about women.

“In disasters, sometimes people look at women as victims,” Lea says. “With women taking an active role, we see them as empowered members of society that lead their communities in disaster preparedness and coping with climate change impacts.”

“With women taking an active role, we see them as empowered members of society that lead their communities in disaster preparedness and coping with climate change impacts.”

As Lea and her team documented the groups that were taking action on disasters, she was struck by how central women were to the climate preparedness discussion. “Women form organizations and they implement mangrove reforestation activities,” she says.

Leas says women are acting with urgency on climate issues because they are the ones who experience the impacts of climate disasters. “We are witnessing the effects of climate change,” she says. “We see washed-out houses and damaged mangroves. We hear the lived experiences of communities: how climate change is impacting them, their fear of storm surges, how their crops died from drought.”

Through inclusive engagement sessions, Lea builds trust with community leaders and they share their experiences of coping with disasters.

“We work with communities that are subject to constant flooding,” she says. “Every time there is a high-tide, the water enters their houses. Climate change impacts are very real for them; they live through it most of their lives.”

Lea says the extensive engagement with communities as well as evidence-based research informs their publications and that in-turn shapes policies. “Our role conducting evidence-based research is to provide data that can guide policymakers, NGOs, humanitarian workers and people working in disaster risk reduction,” she says. “The data helps them design their program activities or their policies so that it helps communities build back better, be more resilient and be more disaster-prepared.”

“The data helps them design their program activities or their policies so that it helps communities build back better, be more resilient and be more disaster-prepared.”

Lea says the progress can be slow, but she’s pleased that a recent bill in the Senate calls for a government Department of Disaster Resilience in support of localizing disaster preparedness that would seek to reduce disaster risk that drives migration to already overcrowded urban areas where services can be limited.

“Some of the women we engaged with were displaced by typhoons and ended up in urban areas,” she says. “They are climate migrants. They move to the city to find a better life and end up in a highly congested area: a marginalized urban community in metro Manila.”

Lea says this instinct to escape the devastation at home and seek work in the city can leave women vulnerable to health hazards and even more climate disasters.

“In the city women are relying on a degraded environment,” Lea says. “The urban poor or slum-dwellers represent some of the most vulnerable populations because of the absence of alternative options. They live in dangerous locations that are vulnerable to climate change effects. These locations are often lacking protective infrastructure like drainage or the means to cope with the impacts of disaster.”

Lea says the unhygienic conditions can create further risks. “We see women living in conditions that have no shower facilities and no drinking water,” she says. “The settlements have a lot of garbage, they are densely populated areas and constantly exposed to disasters.”

Lea is worried that climate change could accelerate this trend of displacement and leave many women in danger.

“As climate change intensifies, there is a chance that more people from rural areas will move to urban areas,” she says. “We see women getting even more exposed in an area where they have no support system.”

Photo: Mark Toldo

She says a coordinated effort is needed to address the issue of climate migration and it needs to start with discussions at the local level on how to reduce risk in urban and rural communities.

“If rural areas were disaster resilient, there is no need for women to go to highly congested areas in an urban setting where they will be more exposed to climate disasters,” Lea says. “We need to help people understand the risks and build systems to help women stay connected to their communities.”

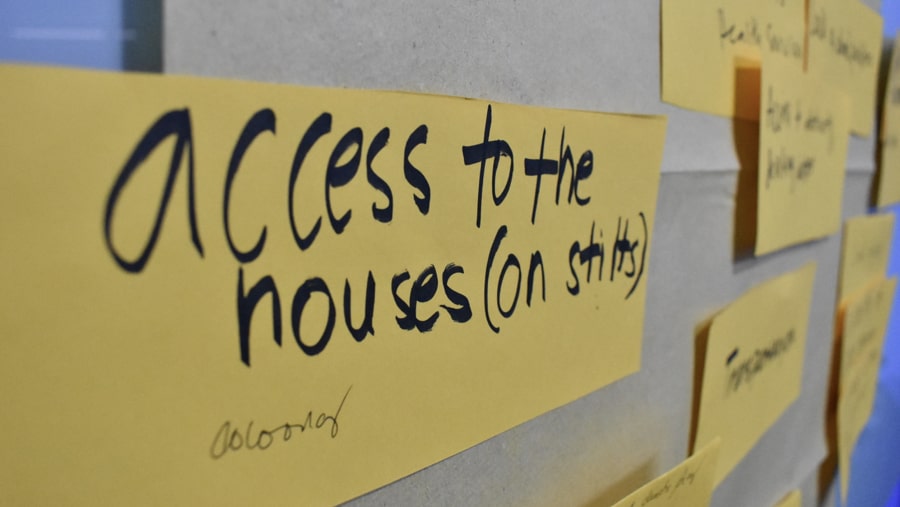

Lea says the combination of data and stories from the community consultations means that women’s concerns are addressed by development and humanitarian efforts. “It’s about ensuring that women's needs during a disaster are reflected in project designs,” she says. “We want the voices of the community to be amplified by those working on policies and designs of infrastructure.”

“It’s about ensuring that women's needs during a disaster are reflected in project designs. We want the voices of the community to be amplified by those working on policies and designs of infrastructure.”

Lea has seen many instances where architects and planners have pursued forced relocation for residents without listening to the community. She has seen first hand when teams of experts do vulnerability studies and find that the area is highly vulnerable to disaster and then push to relocate communities.

In one of the coastal communities that Lea worked with, the people near a landslide-prone mountain were relocated to another area. Despite government warnings, the people moved back to the hazard-prone area because of their familiarity with the neighborhood, attachment to the community and access to jobs as reasons for staying.

“Most people do not want to relocate,” she says. “Our study found that 70 percent of people said they would want money to improve their houses to better withstand the damages of typhoons. If people are given the chance they would rather stay in their own place rather than move somewhere else.”

Lea is also researching the power of community cohesion and ‘sense of place' because she feels it is an aspect of resilience that should be considered by policy-makers and planners in order to build back better.

“It’s about finding ways to involve the community in making the designs and finding out what they want in their communities.”

With this critical insight and perspective, the next step is to engage architects and planners to find solutions to help people improve their homes.

“This is where architects' creative thinking for designing disaster-proof houses can come out,” she says. “It’s about finding ways to involve the community in making the designs and finding out what they want in their communities.”

Lea says the process of engaging communities about their concerns creates the spaces for women to exercise leadership.

“Women in the communities are active participants in building disaster preparedness,” she says. “We need to reach out to them and support them.”

Join the Women’s International Network on Disaster Risk Reduction

The Women's International Network on Disaster Risk Reduction (WIN DRR) is a professional network to support women working in disaster risk reduction, in all their diversity. WIN DRR promotes and supports women's leadership in disaster risk reduction across the Asia Pacific region, and aims to reduce the barriers faced by women and empower them to attain leadership and enhance their decision-making in disaster risk reduction. WIN DRR is supported by UNDRR and the Government of Australia.

Learn more

Program on Resilient Communities website

Perceptions of disaster preparedness (nationwide survey in the Philippines, first of its kind)

Visual Guide: Perceptions on vulnerability

Network analysis of DRR and resilience actors in the Philippines

Introduction to socio-ecological resilience

About the author:

Lea Ivy Manzanero works as the Project Lead for the Program on Resilient Communities of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative. She’s based in Manila but works in communities across the Philippines to develop evidence-based research on the impacts of climate disasters on vulnerable groups. Her work shapes decisions by policymakers and disaster managers by mixing data with grassroots perspectives.