The changing nature of the gender inequality of risk in the Caribbean

Moving beyond the “victim lens” and engaging women more effectively.

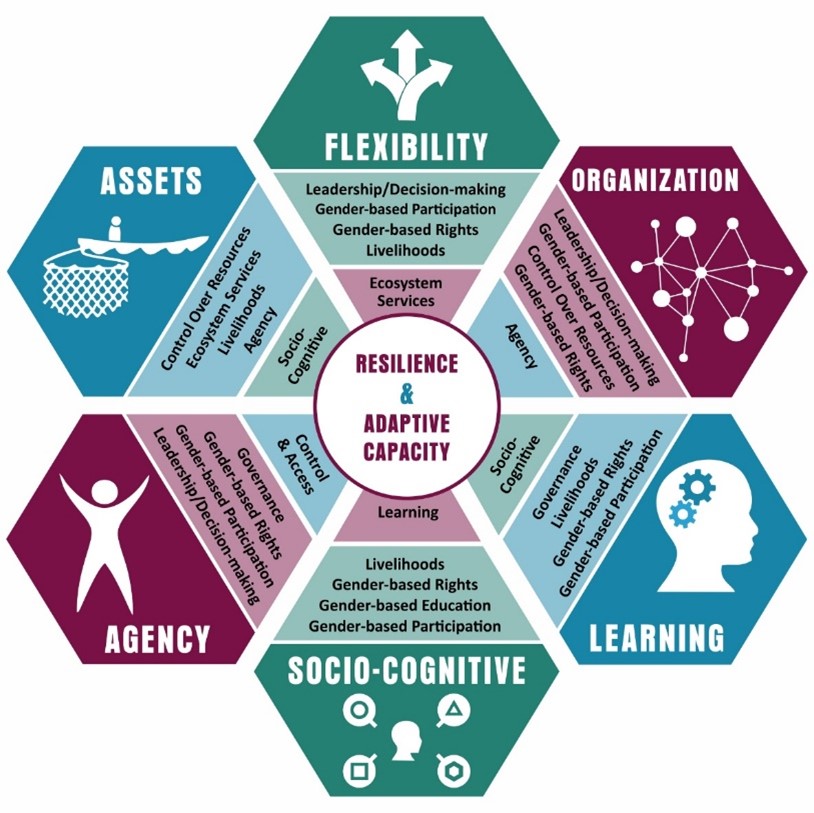

My work with the UN Women’s Multi-Country Office in the Caribbean (MCO Caribbean) has touched upon a variety of issues including the gender inequality of risk arising from disaster impacts such as ashfall from the recent volcanic eruption, climate change, and COVID-19. Several lessons and insights emerge from the lens of the Caribbean experience, which are critical to the ability of these Small Island Development States (SIDS) to build resilience in times of increasing uncertainty (see Figure 1).

Multiple health sector challenges

Many countries in the Caribbean have had a relatively mild COVID-19 pandemic, health system wise, until recently. In fact, in late 2020, dengue fever presented a more serious concern for the health of Vincentians with more deaths and more cases in a short period of 2 months than the entire COVID-19 pandemic up to that point. The dengue outbreak was attributed to environmental health issues notably poor water storage practices. The care burden including recovery from infection was expected to fall largely on the shoulders of women in the household and the community. Some of the affected communities are amongst the poorest and were also most impacted during the most recent extreme events in 2013 and 2014 in terms of physical loss and damage as well as livelihoods.

Ripple effects

The fallout from the ashfall from the La Soufrière volcano eruption in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, in April and May 2021, extended to Barbados and affected farmers – both women and men – in ways that were unexpected. Water supply and forage for livestock (including bees), were affected. Human systems and ecosystems were similarly challenged to respond. A glaring insurance gap, particularly for farmers, has led to a growing call for access to climate risk micro-insurance.

Education – labour market – asset building pipeline

The education – employment – asset building pipeline is not working for women and men in the same way. Education has not guaranteed well-paying jobs for women, and they often work in low-paying jobs. This is not new, but the cost is emerging now in ways that are undeniable. Job losses for women have often exceeded those of men, and women do not have the same rate of asset accumulation and are hence disproportionally impacted by disasters. Men have better access to some of the more resilient sectors such as construction, and therefore can access jobs that require specialised skills via vocational training which often pay more per hour. These skills provide opportunities even when crises strike such as ashfall, while the burdens in other professions that are female-dominated are intensifying amidst resource shortages. There is also a visible parenthood impact gap. A review of 2021 the Women, Business and the Law Report, looking only at for Caribbean countries, shows that parenthood is the weakest area of legal protection for working women and one of the areas with the least progress. Specific labour-market vulnerabilities including harassment also exist for some categories of workers begging the question if social organisation (i.e. organising of themselves into a cohesive group that elevates the voices of these workers as well as facilitating lobbying and advocacy) might not be a possible solution that needs more consideration.

Moving beyond the “victim” lens

We need to engage differently and more effectively with Persons with Disabilities (PWDs). PWDs face intersectional challenges, and hence there is much we can also learn from this community in terms of resilience. In Dominica for example, the Dominica Association of Persons with Disabilities has turned their experience from Hurricane Maria into a public service announcement (PSA), a powerful example of agency, that speaks to issues of risk perception as well as how we learn from our experiences, good and bad. One key recommendation emerging from this experience is the value of a personal disaster plan. My engagement with them taught me that “resilience starts with us.”

The nature of risk is changing

The challenges facing Caribbean countries and Caribbean women and girls are not just extreme events but cascading and multiple hazards, which challenge any household, community and country in finding a path to resilience. Risk is no longer solely economic, social or environmental, it is often a combination of all three. The COVID-19 pandemic has showed this changing dynamic. These challenges require having solid foundations of society, the economy, and ecosystems, working in sync. The UN Women Multi Country Office in the Caribbean is actively working with other UN agencies and other partners to adjust and mainstream these lessons in its ongoing and future work and as part of the UN Coordination system and framework.

About the author:

Leisa Perch is a Coordination Consultant with UN Women MCO Caribbean and is supporting several of their programmes including the EnGenDER project and the Spotlight Initiative. She is also the CEO of SAEDI Consulting (Barbados) Inc. She is a gender and environment consultant with more than twenty-years of experience and a former Deputy Representative of the UN Women’s Mozambique country office and a former Policy Analyst with UNDP.